In my previous post, I discussed the impact that a Democratic president and Congress will have on Christian religious freedom in the United States, given the rapid radicalization of the American Left. I argued that persecution of Christians is quickly increasing, and that it is only a matter of time before biblical Christianity will be made illegal in the United States. Although some people suggest that current trends could be permanently reversed through political activism or a nationwide spiritual revival, I stated that biblical prophecy gives a very bleak spiritual outlook for the United States. However, before discussing the subject of the United States in biblical prophecy, some preliminary matters must be addressed. These include (1) basic concepts and definitions in biblical prophecy, and (2) the question of whether we can know that we are living in the end times.

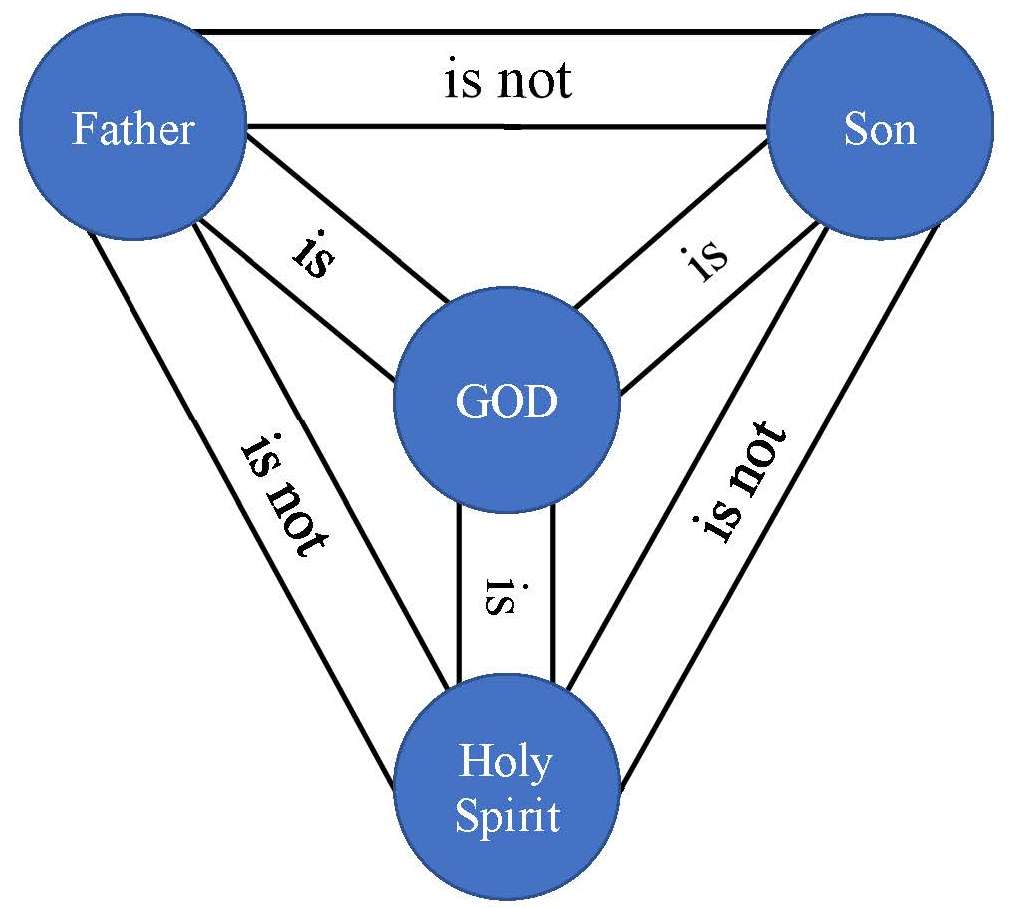

The doctrine of last things is called eschatology, and the final period of world history is called the eschaton. Major positions in eschatology can be defined by views of the millennium. Revelation 20:1-7 refers six times to a period of 1,000 years, at the beginning of which Satan is bound, and during which resurrected saints reign with Christ over the earth. This 1,000-year period is called the millennium, or the “millennial kingdom.” The millennium is also called the “messianic kingdom” because of biblical promises of a future reign of the Messiah (Christ) over the whole world from David’s throne in Jerusalem. The belief that Revelation 20 describes a literal thousand-year future reign of Christ on the earth is called premillennialism. According to premillennialism, the millennium has not yet begun, and Christ’s second coming to earth will happen before the millennium starts. The second coming is the return of Christ to the earth in power and great glory, judging the wicked and saving the righteous (Rev 19:6-21). The millennium follows the second coming. At the end of the thousand years, there will be a final rebellion against God, which He will crush without difficulty (Rev 20:7-10). Following this, there will be a final resurrection and judgment (Rev 20:11-15). Then eternity begins—eternal punishment for the wicked, and eternal bliss for the righteous (Rev 21:1–22:5).

There is a general consensus among premillennialists that the millennium will be immediately preceded by a seven-year period of time called the tribulation (Revelation 4–19). The tribulation will be a time when the earth is plagued by God, while God’s people are persecuted by satanic leaders known as the antichrist and the false prophet. According to the doctrine called the pretribulational rapture of the church, Christian believers will be removed from the earth and taken to heaven before the start of the tribulation period, which means that the saints who are persecuted during the tribulation are ones who were converted to Christianity during the tribulation period itself.

The rapture is an event in which Christ will come to the sky above the earth in a manner that is visible only to Christians. In an instant, both dead and living believers from the Church Age will be given glorified bodies and will be taken to heaven by Christ. The basis for the doctrine of the rapture is three passages in the NT that describe a return of Christ that is distinguished in important ways from biblical descriptions of the second coming. These three passages are John 14:1-3, 1 Corinthians 15:51-52, and 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18. The rapture also appears to be indicated in Revelation 4:1.

Although premillennialists hold differing views on the timing of the rapture of the church, the view called pretribulationism has long been recognized as the one that follows the most literal and consistent interpretation of prophetic passages, and therefore the one that is most faithful to the premillennial outlook. As its name suggests, pretribulationism teaches that the rapture of the church will occur before the tribulation. Although some pretribulationists posit a gap of time between the rapture and the start of the seven-year tribulation period, the view that is most consistent with the dispensational distinction between Israel and the church (explained below) is that the seven-year tribulation period begins immediately after the rapture (cf. Dan 9:24–27; Rom 11:17-27).

In summary, the pretribulational, premillennial viewpoint teaches the following basic order of end time events: (1) the rapture of the church; (2) the seven-year tribulation period; (3) the personal, visible return of the Lord—the second coming; (4) the thousand-year reign of Christ—the millennium; (5) the final judgment and eternal state.

The reason why Christians hold different views of biblical prophecy is not because the Bible is unclear or contradictory. The different approaches to biblical eschatology are based on different methods of interpreting the Bible, or hermeneutics. It has long been recognized that following the literal hermeneutic results in a premillennial understanding of biblical eschatology, because the thousand-year future reign of Christ on earth (Revelation 20:1-7) is understood literally. The literal hermeneutic is a method of interpretation which “gives to each word the same exact basic meaning it would have in normal, ordinary, customary usage, whether employed in writing, speaking, or thinking” (J. Dwight Pentecost, Things to Come, p. 9). The literal hermeneutic allows for due recognition of figures of speech and metaphors as indicated by the context. The bottom-line rule for the literal hermeneutic is the common sense, natural meaning of communication. At times there will be disagreement as to what this is, but the basic principle is clear.

The Bible itself does not formally teach a hermeneutic. There is little discussion, particularly in the Old Testament, of the method by which the reader is to understand the text. This implies that the language used in the Bible is to be understood in exactly the same way as language used in ordinary communication—no special method is needed. This is confirmed by the way in which biblical writers interpret other biblical texts. For example, in Daniel 9:1-23, the prophet Daniel reads the prophet Jeremiah’s prophecy of a seventy-year exile (Jer 25:11-12; 29:10), and, realizing that the seventy years were almost up, Daniel prayed to God for the restoration of divine favor to Israel. There was no question in Daniel’s mind as to whether the seventy years were literal years. Daniel had no doubt that the prophecy would in fact be fulfilled, that it would be fulfilled literally, and that it would be fulfilled in exactly seventy years. Daniel did not take seventy years as merely a metaphor for a long period of time, or as a symbolic expression of God’s graciousness, or as a mere approximation. He took the seventy years to mean seventy years. He did not wonder whether the meaning of the prophecy could change through time, or whether there might be uncertainty as to its fulfillment. He had no question as to the beginning point of the seventy years, even though there were three different deportations from Jerusalem. To him, the prophecy was clear, direct, specific, and understandable. Daniel’s interpretation of another prophet’s prophecy provides a template for our own method of interpreting biblical prophecy.

A foundational assumption of hermeneutics for a believer ought to be the verbal, plenary inspiration of the Bible—that is, that every word of the Bible is inspired by God. This makes the Bible the authority, not the mind of the interpreter. The interpreter must let the text speak for itself; he must try to find what the text says, rather than inserting his own ideas into it. The only way to do this is to apply the literal hermeneutic. Alternative hermeneutical methods, such as the allegorical hermeneutic, subjectively put the interpreter’s own ideas into the biblical text and make the interpreter a greater authority than the text itself.

A natural implication of premillennialism and the literal hermeneutic is dispensationalism. Dispensationalism teaches that the Christian church is distinct from Israel. That is, the Jews are still God’s chosen people, and Gentile Christians are not “spiritual Israel.” The blessings that God promised to ancient Israel will be fulfilled to ethnic Jews—God’s promises to Israel have never been canceled or transferred “spiritually” to the church. Dispensationalists usually view the modern state of Israel as a step in the fulfillment of God’s promised eschatological restoration of the Jewish people. Also, because God gave the Jewish people the right to possess the land of Canaan forever (cf. Gen 17:8; 48:4; Jer 31:35-40; 33:19-26), dispensational Christians have been some of the strongest political supporters of the state of Israel. Many dispensational churches are also active in Jewish evangelism, as they seek to be part of God’s work to restore His people spiritually as well as physically.

The major alternative to premillennialism is amillennialism, which as its name implies teaches that there will not be a literal thousand-year kingdom of God on the earth. Inherent in amillennialism is a conflict with the literal hermeneutic. This is because there is a period of “a/the thousand years” mentioned six times in Rev 20:1-7. The Bible states that the saints will reign with Christ (Rev 20:4, 6) on the earth (Rev 20:8-9) during these thousand years. This description matches numerous Old Testament prophecies of an earthly kingdom, promised to Israel, over which the Messiah will reign (e.g., Isa 65:17-25; Ezekiel 40–48; Dan 7:13-14). Oswald T. Allis, a prominent amillennialist, concedes that “the Old Testament prophecies if literally interpreted cannot be regarded as having been yet fulfilled or as being capable of fulfillment in this present age” (Oswald Allis, Prophecy and the Church, p. 238). Another amillennialist says, “Now we must frankly admit that a literal interpretation of the Old Testament prophecies gives us just such a picture of an earthly reign of the Messiah as the premillennialist pictures” (Floyd Hamilton, The Basis of Millennial Faith, p. 38). However, amillennialism rejects the literal hermeneutic in favor of the allegorical hermeneutic, which “is the method of interpreting a literary text that regards the literal sense as the vehicle for a secondary, more spiritual and more profound sense” (Pentecost, Things to Come, p. 4). A common criticism of the allegorical method is that “the basic authority in interpretation ceases to be the Scriptures, but the mind of the interpreter” (Pentecost, Things to Come, p. 5). Another criticism of the allegorical method is that “one is left without any means by which the conclusions of the interpreter may be tested” (Pentecost, Things to Come, p. 6). While non-literal hermeneutical systems go by many names today, they are all varieties of the allegorical hermeneutic, designed to replace the plain teaching of Scripture with man’s ideas (cf. 2 Cor 11:3). By using the allegorical hermeneutic to turn physical promises into spiritual ones, amillennialists teach that the promises God made to Israel in the Old Testament have been transferred to the predominantly Gentile church, and that ethnic Israel will not experience a political restoration in the eschaton—God has cancelled His promises to the Jewish people and rejected Israel as a nation forever because of their crucifixion of Jesus. Amillennialists specifically deny that the Jewish people will have a place of special privilege in a future messianic kingdom. In fact, amillennial Christians have frequently persecuted the Jews, as they observe Jewish hostility towards the Christian gospel without balancing this with the recognition that Israel remains a special object of God’s love due to the promises God made to the Jews’ forefathers (Rom 11:28). Many amillennialists today are distinctly hostile towards the modern state of Israel, perhaps because Israel’s political restoration supports the dispensational claim that the Jewish people have a special place in God’s prophetic program.

In summary, the literal hermeneutic is the only method of interpretation that can reveal what biblical prophecy means, because all other hermeneutical methods subjectively put the interpreter’s own ideas into the biblical text. Application of the literal hermeneutic results in an eschatological framework that is:

- Pretribulational—recognizing that the present era of biblical history will end with the rapture (removal to heaven) of believers who are part of the Christian church, and that this will be followed by the final seven years of God’s program for Israel before the second coming of Christ, as described in Daniel 9:27.

- Premillennial—recognizing that the kingdom of God is not a present spiritual reign of Christ in the hearts of Christians, but is rather a literal (political) future kingdom. Although Christ will reign forever, the first phase of His kingdom will last for 1,000 years, and will begin after Christ returns to the earth in power and great glory at the end of the seven-year tribulation period, destroying the wicked completely and bringing the righteous into His kingdom.

- Dispensational—recognizing that the nation of Israel continues to have a special place in God’s plan, and that Israel will be the political and spiritual center of Jesus Christ’s coming kingdom on the earth.

With this basic introduction to biblical prophecy, we are now ready to discuss the issue of whether our current situation in history is close in time to the tribulation period. This will be the subject of my next post.

Enjoy this content? Buy me a coffee, or support this blog via a PayPal donation.