The rapture is one of the most important, most controversial, and most poorly understood eschatological doctrines. In this post, I would like to explain from the Bible the reasons why I believe in the pretribulational rapture of the church.

The word “rapture” refers to a “carrying away” or a “snatching away.” The English word “rapture” comes from the Latin noun raptura, which is etymologically related to the Greek verb ἁρπάζω that is used in 1 Thessalonians 4:17. The rapture is an event in which Christ will descend from heaven to the sky above the earth, accompanied by a trumpet blast and the shout of the archangel Michael (1 Cor 15:52; 1 Thess 4:16). Both living and deceased Christians will instantaneously be given glorified resurrection bodies and will be caught up into the clouds, where Christ will lead them back to heaven. Only Christians will see Christ at that time, though the entire world may hear the trumpet blast.

As its name suggests, pretribulationism teaches that the rapture of the church will occur just before the start of the tribulation. The tribulation is a seven-year period corresponding to Daniel’s seventieth week that occurs immediately prior to the second coming of Christ. Before establishing the timing of the rapture, it is imperative to first establish that the coming of Christ for the rapture of the church is an event that is distinct from the second advent, and therefore the rapture is not posttribulational. There are three passages in the New Testament that teach about a return of Christ that is different from the second coming. These three passages are John 14:1-3, 1 Corinthians 15:51-52, and 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18 (see also Rev 4:1).

John 14:1-3

In the Upper Room discourse, which begins in John 13:31, Jesus is preparing the eleven disciples for His departure. At the end of John 13, Jesus mentions that He is going away, which prompted a confused reaction from Peter, who did not understand why he could not go with Jesus. Jesus proceeds to explain in John 14:1-4 that He is not going on an earthly journey, but on a journey to the Father, where He will prepare a place for them, and where they will be reunited forever. In John 14:2-3, Jesus says, In my Father’s house are many dwelling places. If it were not so, I would have told you, for I go to prepare a place for you. And if I go and prepare a place for you, I am coming again, and will take you to Myself; that where I am, there you may be also. Jesus says He will take the disciples (who are Church Age believers) to Himself and will take them to the place where He is, to His Father’s house. The Father’s house is the place where God the Father dwells, which is heaven. In other words, Jesus will come to earth, will resurrect the disciples and (by extension) all those who are part of the church (He is not just coming for the Eleven—cf. John 12:26), and will take them to heaven. In contrast, at the second coming, Jesus will come to the earth and stay on the earth. He will establish an earthly kingdom, and therefore will not take the saints back to heaven with Him, but will instead give them an earthly inheritance. These contrasts demonstrate that it is impossible that John 14 is speaking of a resurrection at the second advent.

1 Corinthians 15:51-52

The second of the three major rapture passages is 1 Corinthians 15:51-52. That passage reads as follows: Behold, I tell you a mystery: we will not all sleep, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised incorruptible, and we will be changed. In verse 51, Paul says that the resurrection of believers he describes in these verses is a “mystery,” meaning that it is something that was not previously revealed. It cannot therefore occur in conjunction with the second advent, which is spoken of throughout both the Old and New Testaments. The rapture was not revealed in the Old Testament, even if it could be deduced by implication, because it is something that is specifically for the church, and not for Israel. Thus, the translation of living saints to heaven is never revealed in the Old Testament, either. These verses also add the important detail that both dead and living believers will be raised, which creates a serious problem for posttribulationism—there would be no one left to enter the millennium in a mortal body if all believers are given glorified bodies and all unbelievers are killed. More will be said about this problem later on, as it is one of the chief difficulties in the posttribulational system. Thus, there are three reasons why 1 Corinthians 15:51-52 must be speaking of the rapture: it is presented as a mystery; it includes the resurrection of Church Age saints (“we”); and it includes the resurrection both of the living and the dead. Note that the “last trumpet” is not the seventh trumpet, which is sounded at the midpoint of the tribulation (Rev 11:15), nor is it the trumpet that is sounded at Christ’s second coming (Matt 24:31)—it is rather the last trumpet for Christians, or the trumpet blast which signals the end of the Church Age.

1 Thessalonians 4:13-18

The last of the three major rapture passages is 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18. Verse 13 reads, But we do not want you to be uninformed, brothers, about those who are asleep, so that you may not grieve as do the rest, who have no hope. The Thessalonians, like the Corinthians (1 Cor 15:12, 18), did not know that dead believers would be resurrected. This is interesting in light of 1 Thessalonians 1:10 and 5:1-2, which state that the Thessalonians were fully aware of apostolic teaching concerning the second coming of Christ, and they were in fact waiting for His coming. Thus, they correctly understood that living believers would be saved alive at the second coming, but they did not know what would happen to those who died beforehand. Paul teaches them about the rapture because that is when all Church Age believers will be raised.

Verse 14 continues: For if we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so God will bring with Him those who have fallen asleep in Jesus. The term “in Jesus” refers only to the church, not to OT saints. Thus, this passage is describing a resurrection of Church Age believers only. This is different from the second coming, since Daniel 12:1-3 asserts that OT saints are raised at the end of the tribulation period. Verse 15: For we say to you by the word of the Lord, that we who are alive, who remain until the coming of the Lord, will not precede those who have fallen asleep. Again, this is a resurrection in which both living and dead believers are raised, so if it was posttribulational there would be no one left to populate the millennial kingdom with mortal bodies. Verses 16-17: For the Lord Himself will descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trumpet of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who remain, will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air; and so we will always be with the Lord. Notice that in the coming of Christ that Paul describes, believers will meet the Lord in the air. This is in contrast to descriptions of the second coming, in which the saints are portrayed emerging from heaven to return to the earth with Christ (Rom 8:19; Col 3:4; 1 Thess 3:13; Jude 14-15; Rev 19:14). How could the saints come from heaven with Christ if they are not raptured until He comes? First Thessalonians 4:16-17 says we will meet the Lord in the air after He has already descended from heaven. The rapture therefore must happen at a different time than the second advent, before the second advent.

Finally, in v. 18, Paul writes, Therefore comfort one another with these words. In both the Old Testament and the New Testament, the nation of Israel is warned about the sufferings they will endure during the tribulation period. The church is not. When Paul tells the Christians in Thessalonica that the coming of the Lord will be a great comfort to them, he does not say anything about it being preceded by the tribulation period, which would not be so comforting. He does not warn them to be on the alert for Christ’s coming lest they be judged, or to watch for the signs Christ is just about to return, or to prepare to endure the turmoil of the tribulation period—which is completely unlike the Olivet Discourse and other second coming passages.

It is also interesting that Paul says the Thessalonians were ignorant about Christ’s coming for His church, yet he says in the very next paragraph that they were not ignorant about the second coming. He says in 5:1-3, But concerning the times and the seasons, brothers, you have no need for anything to be written to you. For you yourselves know perfectly well that the day of the Lord comes like a thief in the night. When they are saying, “There is peace and security,” then sudden destruction comes on them, as labor pains on a pregnant woman; and they will not escape. Paul also referenced the second coming twice before in this letter, in 1:10 and 3:13, and he speaks as though the Thessalonians knew about it. This demonstrates that the rapture is an event that is distinct from the second coming.

None of the rapture passages contains any description whatsoever of the judgment of the wicked, or indicates that there is a judgment of the world at the time of the rapture. There is no indication that Christ is coming to set up His kingdom at that time. There is no judgment of Satan, Israel, the nations, the antichrist, or the false prophet. The world and the universe are not destroyed. All that happens is the resurrection of Church Age saints. On the other hand, every passage that describes the second coming describes the cataclysmic judgment associated with it, while none of the second coming passages describes a resurrection of living believers or even a resurrection of Church Age saints. All of the major second coming passages are set in the context of the end of the tribulation period, while none of the rapture passages says a word about the tribulation period. The rapture and the second coming are therefore two distinct events, and the rapture is not posttribulational. Other distinct characteristics of the rapture include its description as a mystery and the return of Jesus Christ to heaven afterwards.

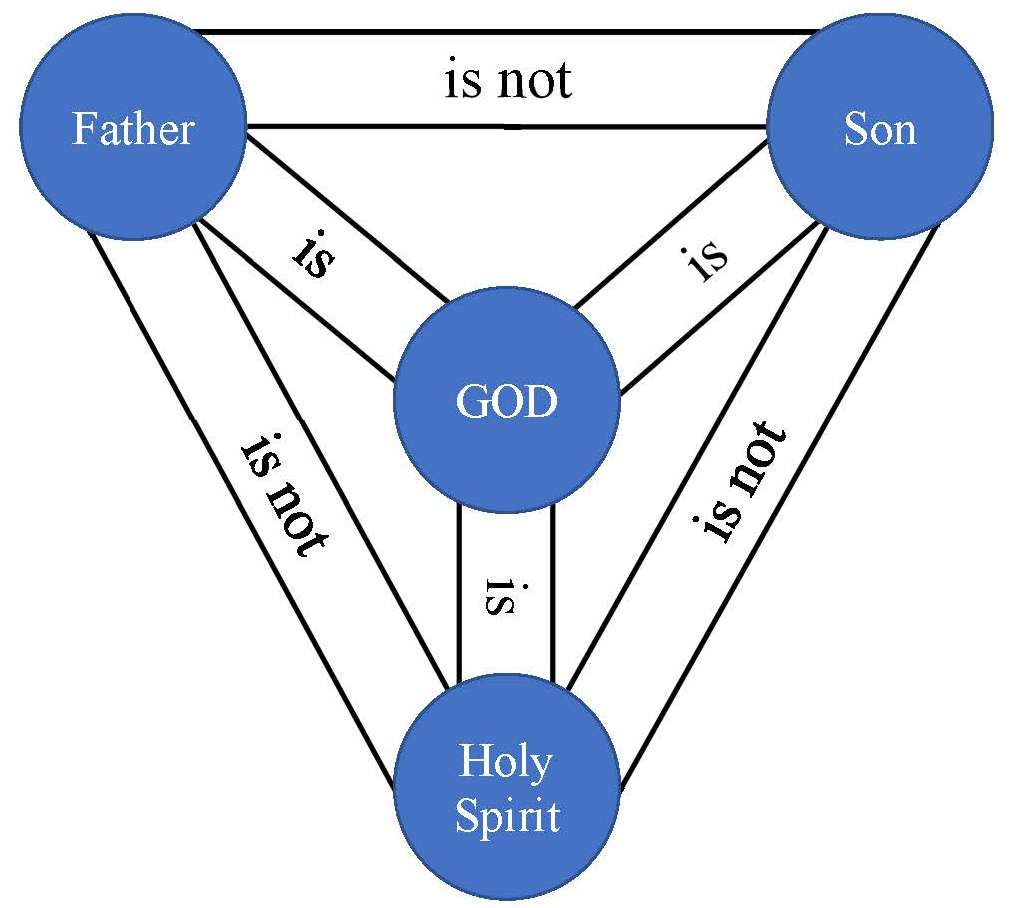

The distinction between Israel and the church

Having established, then, that the rapture is an event that is distinct from the second advent, and that precedes the second advent, let us now consider the evidence that the rapture occurs before the tribulation period, i.e., immediately prior to the start of Daniel’s seventieth week. One of the strongest arguments for this is the distinction between Israel and the church. Israel is still God’s chosen people (Gen 17:7-8, 19; Isa 49:14-15; 54:10; Jer 31:35-37; 33:23-26; Rom 11:1, 28-29). He has not abandoned them—in fact, He has brought them back to their land and protected them there. But during the Church Age—the time from Pentecost until the rapture—Christ is building His church primarily through Gentiles (Acts 13:45-48; 28:28; Rom 10:20-21). The church is never called “Israel” in the Bible, and Israel is never called “the church,” since these are two distinct entities, although of course some Jews are also part of the church.

Daniel 9:24-27 outlines God’s program for the people of Israel and the city of Jerusalem from the issuing of the decree to rebuild Jerusalem until the coming of the messianic kingdom. The length of His program is seventy weeks of years, or 490 years: “Seventy weeks are determined for your people and for your holy city. . . ” (Dan 9:24). Sixty-nine weeks, or 483 years, completed the time from the issuing of the decree until the crucifixion of Jesus by the Jewish people and their leaders (cf. Zech 12:10; Matt 27:24; Acts 2:36; 4:10). After Israel rejected the Messiah, God temporarily switched the primary dispensational focus of His program to the Gentiles, who form the bulk of the church. Since Daniel 9:24-27 is a prophecy of God’s program for Israel, the Church Age is not included in the seventy weeks; there is only an indefinite gap. According to Daniel 9:27, God’s program for Israel is finished in one week, the seventieth week, which is the tribulation period. Hence, God will resume His program for Israel seven years before the second advent, or at the beginning of the period we call the tribulation. The resumption of God’s program for Israel implies the removal of the church, for God has made the church the focus of His salvific program in this age. Pretribulationism is the only view of the rapture that maintains the unity of Daniel’s seventieth week as a time when the dispensational focus of God’s program returns to Israel.

According to Romans 11:25-26, Israel has experienced a partial hardening “until the fulness of the Gentiles has come in.” After that, their hearts will no longer be hardened, and “all Israel will be saved.” The fulness of the Gentiles comes in when the church is taken to heaven at the rapture. Hence, God will resume His program for Israel immediately after the rapture. That this is immediate is proved by the use of the word “until” (ἄχρι) in Romans 11:25: if Israel’s partial hardening occurs only until the rapture, then it is taken away immediately afterward (“. . . and so all Israel will be saved”—v. 26).

That God will resume his program for Israel immediately after the rapture can be deduced logically, even apart from Romans 11:25-26. God would not remove the church unless there were some people of God to replace it with, for He will not cease to work His program. There is only one candidate for the replacement of the church, and that is Israel (Rom 11:23-24). Hence, when the church is removed, its role is restored to Israel. Again, Daniel 9:27 shows that God’s program for Israel is finished in one week, or seven years.

All the biblical descriptions of the tribulation period show that it is focused on Israel, not on the church, and therefore the church must be removed at the start of the tribulation. The first three chapters of the book of Revelation mention the church some 19 times, yet the church is not mentioned one time in Revelation 4–19, which describes the tribulation period. However, 144,000 evangelists from the twelve tribes of Israel are given a prominent place in Revelation 7 and 14, and Revelation 11 describes ministry of the two witnesses in the city of Jerusalem. Satan singles out Israel for special persecution in Revelation 12, and Israel is specially protected by God. The main battle at the end of the tribulation period is centered in the land of Israel (Rev 16:16). Zechariah 12–14 speaks of ethnic Jews living in Jerusalem at the time of the final battle, with Christ returning to rescue His people and destroy their enemies (cf. Dan 12:1). Passages in Revelation 4–19 contain many references to “saints” and “the elect,” but not to “the church” or those who are “in Christ.” Revelation 19 refers to the bride of Christ, but this is a reference to saints who are in heaven, not on earth. The indication, then, is that the focus of God’s program will return to Israel in the tribulation period. This is confirmed by the Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24–25; Mark 13; Luke 21) and numerous passages in the Old Testament that describe the tribulation as a time of great persecution for Israel. Not one of the many passages in the Bible which describes the tribulation even mentions the church. Zechariah 12–13 describes how many Jews will die in the tribulation, but a remnant will repent and be saved. Daniel 9:24-27 presents the tribulation as the final seven years of God’s program for Israel in this age. Jeremiah 30:7 calls the tribulation “the time of Jacob’s trouble.” How can the tribulation be called “the time of Jacob’s trouble” if it is really the time of the church’s trouble? Both the OT and the NT warn the nation of Israel time and again of the things it will suffer during the tribulation period, yet the church is not warned one time.

Because of these problems, most posttribulationists are not dispensational, and those who are have to hold that there is a gradual transition between the Church Age and a return to the time of God’s primary dispensational focus on Israel. Only pretribulationism makes a clear distinction between dispensations and allows for a Jewish millennium.

Posttribulationism

The major alternative to pretribulationism is posttribulationism. The ideas of a midtribulational rapture, a partial rapture, and a pre-wrath rapture have not enjoyed the widespread support accorded to both pretribulationism and posttribulationism because there is no hint anywhere in Scripture of a coming of Christ during the tribulation period. A coming that ends the tribulation period is clearly taught, but posttribulationism denies that this is a separate event from the rapture. One reason why posttribulationism has been so popular over the centuries is that it is required by the amillennial and postmillennial systems of theology. If the church is defined as believers of all ages, then those who have “fallen asleep in Jesus” (1 Thess 4:14) includes Old Testament saints. Thus, there can be no special rapture for those saved after the day of Pentecost in Acts 2. There is no separate rapture in eschatological systems other premillennialism. On the other hand, the dispensational understanding of Scripture requires some point at which the Church Age ends and God’s program reverts back to Israel.

The arguments given above for pretribulationism are implicitly arguments against posttribulationism. However, a few problems specific to the posttribulational scheme may be noted.

Probably the largest problem with posttribulationism is that it does not allow for unresurrected people to enter the millennial kingdom, because all believers are raised at the rapture and all unbelievers are killed at the second advent. There are a great number of passages which assert that only believers will enter the kingdom, e.g., Ezek 20:33-38; Matt 5:20; 25:31-46; John 3:3; 1 Cor 6:9-10; Gal 5:19-21; 1 Thess 5:3. Possibly the clearest passages are Matthew 13:40-43 and Matthew 25:31-46. The rapture passages assert that both dead and living believers are raised and glorified (1 Cor 15:51-52; 1 Thess 4:16-17). Hence, if the rapture occurs at the end of the tribulation, everyone who enters the millennium does so in an immortal resurrection body.

This is a problem because there are many passages that indicate the presence of people in unresurrected bodies in the millennium. Isaiah 65:20 speaks of people dying in the millennium. Isaiah 65:23 and Ezekiel 47:22 speak of people in the millennial kingdom begetting children, and this is implied in various other verses (Isa 11:6-8; 61:9; Jer 30:19-20; 31:8, 13, 27, 34; Ezekiel 46:16-18; Zech 2:4). Ezekiel 44:22 describes men taking wives in the kingdom. According to Matthew 22:30, marrying and begetting offspring cannot be done in the resurrection body. Various verses describe sacrifices for sin in the millennium (Ezek 40:39; 43:18-27; 44:29; 45:13-25), and acts of sin the millennium (Zech 5:1-4; 14:17-19), showing that there are people in the kingdom who have not yet experienced the perfect sanctification that comes with glorification. Revelation 20:7-9 describes a great rebellion at the end of the millennium in which an innumerable number of people will turn against Christ and assault Jerusalem, resulting in the deaths of all those who have rebelled. This rebellion shows not just that there are mortal men in the millennium, but also that there are unsaved mortal men. The only way the unbelievers could have gotten into the kingdom is by procreation, since only the saved will enter the millennium.

Besides these problems, there are passages that directly state that some people will survive the tribulation period and the second coming. Zechariah 14:5 describes believers fleeing on foot after Christ has returned at the second advent. Daniel 12:1, Zechariah 14:16, and Micah 4:2-3 also refer to survivors of the tribulation period.

Posttribulationists have never been able to resolve the problem of how mortal men enter the millennium, nor can they, for their scheme simply falls apart at this point. The suggestion that some Jews repent as Christ is descending contradicts various verses which teach that there can be no repentance after the midpoint of the tribulation is reached or a person receives the mark of the beast (2 Thess 2:9-12; Rev 14:9-12). When the second coming begins, it is too late to repent; men’s fates are sealed (Matt 7:21-23; 25:10-12, 41-46; Rev 6:12-17).

The major biblical argument for posttribulationism is the claim that the Bible only presents one return of Christ. However, the passages analyzed above describe a return of Christ that is not visible to the entire world, in which Christ does not return all the way to the earth and does not judge the earth. Another argument for posttribulationism that is that pretribulationism is a recent invention, and the church has always believed in posttribulationism. Walvoord notes that “in offering this argument, posttribulationists generally ignore the fact that modern forms of posttribulationism differ greatly from that of the early church or of the Protestant Reformers and are actually just as new or perhaps newer than pretribulationism” (John Walvoord, The Blessed Hope and the Tribulation, 145). Specifically, the strain of posttribulationism that holds that the tribulation is a future seven-year period of time differs from the historic view of most theologians in church history, who spiritualized the tribulation and held that the entire Church Age is the tribulation period. Also, while John Nelson Darby claimed to have developed his teaching on the pretribulational rapture directly from the Bible, it is clear that there were other pretribulationists before Darby, such as a Baptist preacher named Morgan Edwards. Farther back in time, in the early Middle Ages, a document called Pseudo-Ephraim expresses a belief in the pretribulational rapture. Beatus of Liebana, who published the final edition of his Commentarius in Apocalypsin in 786, mentions the “rapture” as if it were common knowledge. See also Francis Gumerlock’s 2002 article and 2013 article, and William Watson’s book Dispensationalism before Darby. On the other hand, prophecy tends to become clearer as the time of fulfillment nears, so the increased popularity of pretribulationism in our day should not be surprising.

Posttribulationists claim that the doctrine of a pretribulational rapture rests on very shaky grounds because it is based largely on inference. However, inferences are different than assumptions, and posttribulationism rests on many unsupported assumptions or assertions. Posttribulationists assume that the church will go through the tribulation period, even though none of the terms that are typically used to refer to the church is used with reference to the saints who are alive during the tribulation period. Posttribulationists have never been able to explain why New Testament writers such as Paul do not warn the church to prepare for the tribulation period, with all of its perils. It seems that the passages in which Paul describes the rapture ought to include a description of the terrible tribulation that will precede it, if indeed the rapture is posttribulational. Another assumption made by posttribulationism is that saints will rise from the dead to meet Christ as He is coming down from heaven. This is never explicitly stated, and in fact Revelation 20:4-6 proves that dead tribulation saints will not be raised until the judgment which follows the second coming. If the rapture is posttribulational, then there is no reference whatever to it in the book of Revelation, in spite of the lengthy, detailed, and sequential presentation of end time events in that book.

Another problem with posttribulationism is that it cannot explain the differences between descriptions of the second coming and descriptions of the rapture. These differences have already been noted. The differences between the coming of Christ for the church and the second advent are very significant, and posttribulationists have not given an adequate explanation for how they can be considered identical.

A final problem with posttribulationism is that it contradicts the premillennial dispensational understanding of Scripture, which is based on a literal understanding of Scripture. If the rapture is posttribulational, it is impossible for there to be people with mortal physical bodies in the millennium, and therefore it is impossible for there to be a literal, physical thousand-year reign of Christ on the earth. No one who believes in a literal millennium can accept a posttribulational rapture without a serious contradiction. Denying the millennium is a major problem, because both the Old and New Testaments are filled with descriptions of a lengthy, literal, earthly kingdom, and Revelation 20 says no less than six times that it will last one thousand years. A denial of the millennium also has much more serious consequences in terms of one’s view of God’s fulfillment of His covenants with Israel, and the completion of Christ’s redemptive work.

Posttribulationism also contradicts dispensationalism in that there is no clear break between the end of the Church Age and the renewal of Israel as the focus of God’s dispensational program. No posttribulationist theologian makes a clear distinction between Israel and the church, which is the sine qua non of dispensationalism. In no way can a dispensationalist accept a posttribulational rapture without seriously contradicting himself.

Posttribulationism also has major practical implications. Should we start digging bunkers and building up a seven-year supply of food to survive the tribulation? Should we try to figure out if the tribulation has already started and whether we should be looking for signs that the second coming is about to happen? Posttribulationism also leads logically to a denial of premillennialism and dispensationalism, thereby undermining a literal approach to interpreting Bible prophecy. I will close with a quote from John Walvoord: “The evident trend among scholars who have forsaken pretribulationism for posttribulationism is that in many cases they also abandon premillennialism. . . . It becomes evident that pretribulationism is more than a dispute between those who place the rapture before and after the tribulation. It is actually the key to an eschatological system. It plays a determinative role in establishing principles of interpretation which, if carried through consistently, lead to the pretribulational and premillennial interpretation” (Walvoord, The Blessed Hope and the Tribulation, 166).

Enjoy this content? Buy me a coffee, or support this blog via a PayPal donation.